A novel deep learning based approach to characterising pedestrian pre-crash posture

This is a review of a paper recently published in and presented at IRCOBI Europe 2020 (International Research Council on Injury Biomechanics). The study involves applying deep learning approaches to the task of classifying pedestrian pre-crash pose. This paper is interesting for a number of reasons; primarily due to the fact that this is the first published attempt to use pose and shape estimation in the field of traumatic injury biomechanics, but also because of the adaptations the authors make to existing pose/shape estimation methods in order to achieve more accurate predictions for the task.

Firsty I’ll provide a little background information on vehicle safety systems. They can be classified as being ‘active’, ‘passive’, or a combination of the two. Active safety systems are onboard electronic devices that are continuously ‘active’ and monitoring to avoid collision occurence, e.g. traction control, automatic emergency braking, blind spot detection. Whereas, passive safety systems are design features or devices that are generally inactive, only taking effect upon collision occurence to reduce injury outcomes, e.g. helmets, seat belts, air bags, vehicle/infrastructural design (softer/energy dissapating impact surfaces). Integrated safety systems are a combination of the two, where there is an element of continuous monitoring which informs the deployment of a passive safety system, e.g. advanced airbag deployment systems.

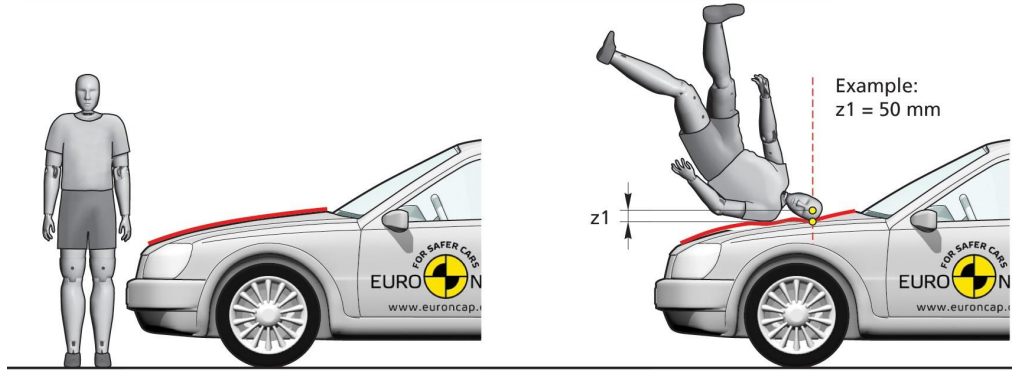

Passive and active pedestrian safety systems are assesed through regulated vehicle type-testing, and by consumer organisations with more comprehensive testing protocols (e.g. EuroNCAP). These tests include assesments of the effects of vehicle front geometry on injury outcomes, and the effectiveness of autonomous emergency braking or evasive steering assistant systems. Current protocols for both active and passive safety systems use simplified pedestrian poses and motions exemplifying an unaware pedestrian walking in front of a vehicle, with no consideration of pedestrian reaction.

However, it is known that pedestrians exhibit certain reactionary postures and motions before being impacted by a car, as described in this paper and other published literature [1, 2].

| Jump | Attempt to avoid | Freeze in place |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Methodology

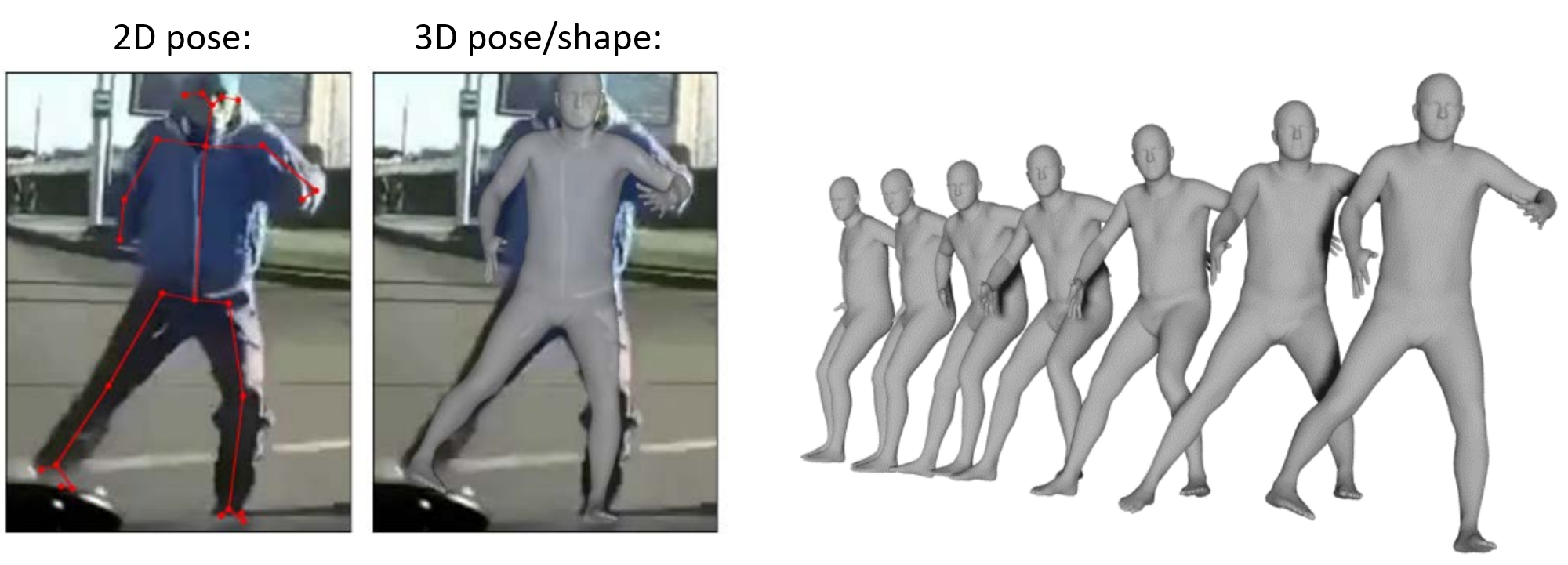

The value of this study lies in its adaptations to an existing pose/shape estimation method called SMPLify [3] to create a toolchain that is capable of quantitatively characterising pedestrian pre-crash posture.

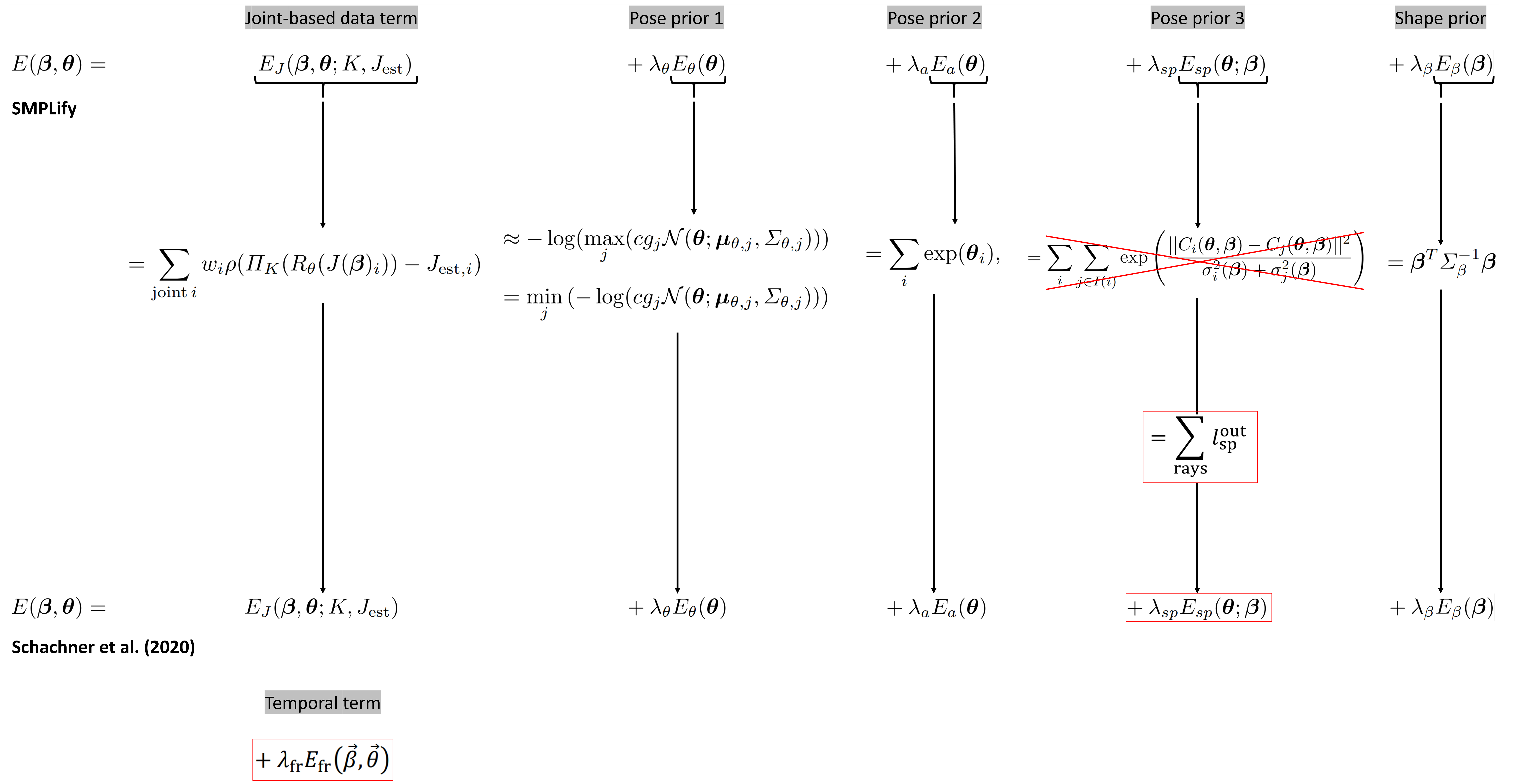

For context, SMPLify fits a statistical human body model called SMPL [4] to an image with DeepCut 2D pose estimates as input [5]. It does this by using an optimization procedure with an objective function containing five error terms. The current study uses SMPLify, with six adaptations to improve pose and shape estimation results for pedestrian pre-crash posture:

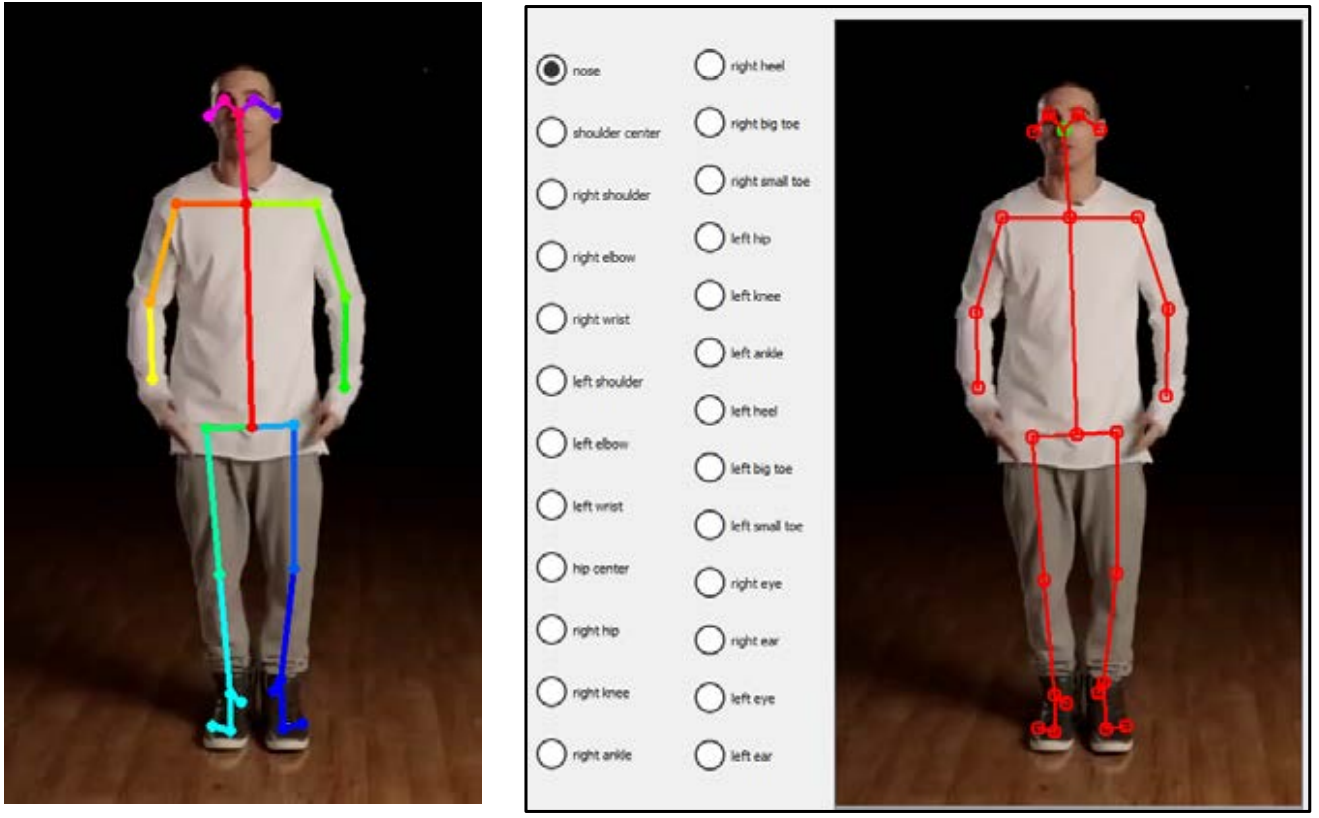

1) The 2D pose estimates are inferred instead using Openpose [6], which outperforms DeepCut.

2) 2D estimates are manually improved on visual inspection.

3) 4) & 5) Three adaptations are made to the SMPLify optimization procedure:

- The shape coefficients (β) are optimised globally over all images in a sequence leading up to the impact.

- Temporal information has been included an error term to be minimized (Efr) i.e. the sum of joint distances across adjacent frames.

- The interpenetration term (Esp) is replaced with a more recent approach which uses rays to detect self-intersection of outer surfaces of the mesh [7].

6) Since the pose prior terms of the optimization procedure penalize unnatural human poses, and mesh interpenetrations, which are likely to occur when a pedestrian is impacted by a car, the results may be conservative for frames in the impact phase i.e. predict less realistic poses. For this reason the weighting factors for the pose and shape terms were relaxed in the final 100 (out of 1000) iterations of the optimization procedure, effectively allowing for less natural poses upon impact.

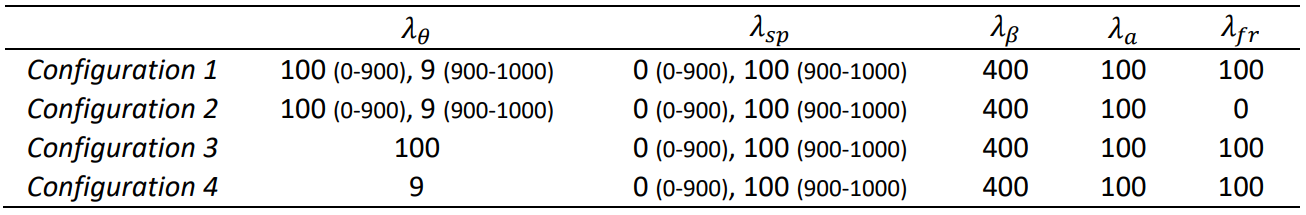

The optimization weights were determined using a commonly used and publicly available motion capture dataset, i.e., Human3.6M [8].

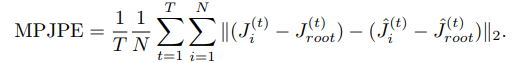

MPJPE or ‘Mean Per Joint Position Error’ is the most commonly used metric for benchmark tests in 3D human pose estimation, i.e. the mean of per joint position error (euclidian distance from ground truth) for all joints.

However, the authors claim that the this metric has limitations, and that in some cases there can be low errors for incomparible poses, i.e., some obviously different poses can have misleadingly low values of MPJPE. So, the authors also investigate elbow and knee angles. Configuration 1 above was selected as having the best overall performance in testing.

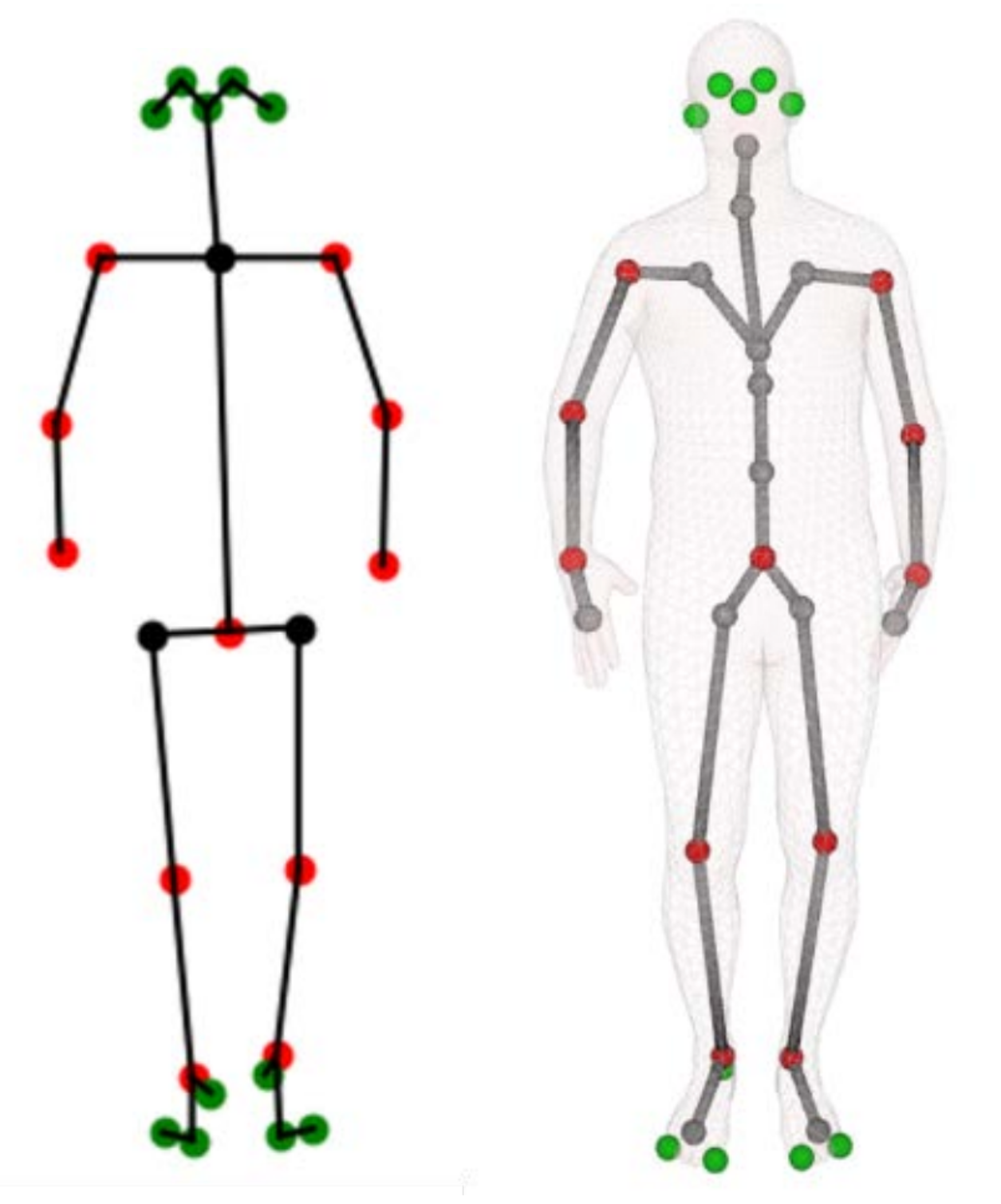

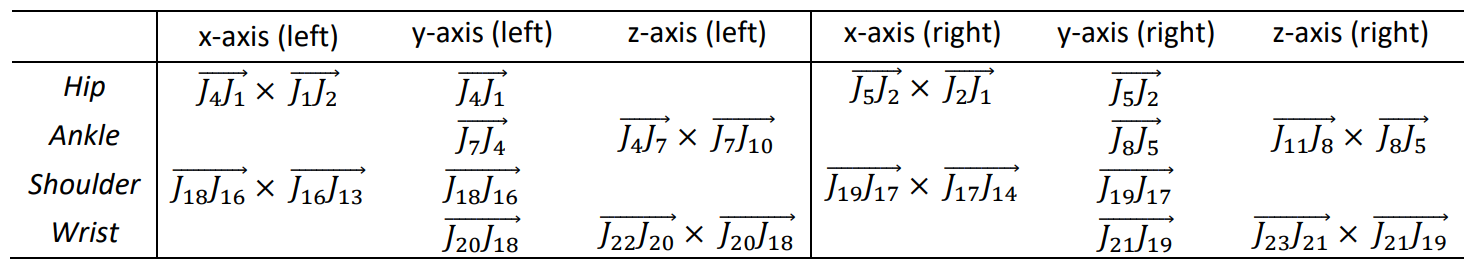

In reporting, joint angles were revised to best approximate the recommendations of the International Society of Biomechanics (ISB) [9, 10]. The table above shows how each joint’s local coordinate system was defined relative to surrounding vectors. For example, the coordinate system of the left hip is defined using two vectors: 1) the vector between J4 and J1 (corresponding to the femur), and 2) the vector between J1 and J2. Then the local x-axis is defined as being in the direction of the cross product of the former and the latter (i.e. rerwards, perpindicular to the plane that the two vectors form), and the local y axis defined as being in the direction of the femur (in the upwards direction).

Discussion

This method improves on all previous attempts to quantitatively characterise pre-impact pedestrian pose, which relied on either volunteer test in simulated environments [1], or visual inspection of crash footage [2]. Approaches like this may help guide changes to the boundary conditions of vehicle safety assesment tests, i.e., provide more representative postures for vehicle type-testing. Though the system is not automatic and requires some manual annotation, this may be a step towards a fully automated toolchain. This technique may also be a first step towards integrated pedestrian safety systems e.g. pose dependent bonnet deployment/active hood systems, or external airbag systems.

3D pose and shape estimation is a rapidly evolving field, and since the submission of this paper, state-of-the-art methods in the area have changed multiple times. Though unlikely to significantly alter the effectiveness of a technique such as this, there is now a new state-of-the-art statistical human body shape model (STAR) [11], which is intended as a replacement for SMPL. There have also been a couple of changes in state-of-the-art for pose and shape estimation, both of which have included the optimization procedure into the 2D pose estimator’s deep neural network, i.e. SPIN (SMPL oPtimization IN the loop) [13], and VIBE (Video Inference for Human Body Pose and Shape Estimation) [14] which in effect improves the 2D keypoint predictions. This study uses semi-manual annotation of 2D keypoints, and though this results in a less automatic pipeline it overcomes known issues with unrealistic openpose predictions. Since 2D keypoint estimates form the backbone of the 3D predictions, any errors in openpose predictions propagate resulting in more unrealistic 3D predictions. It is not described however, whether 2D keypoints are equally or individually weighted in the optimization proceedure after manual annotation has been performed, i.e. the joint-based data term (EJ) in SMPLify uses individual weightings per joint based on certainty in DeepCut predictions. As the authors allude to, it is reasonable to speculate that a similar approach with the optimization procedure included ‘in the loop’ along with the 2D pose estimator may achieve more accurate and automatic results for pedestrian pre-crash pose. The authors also highlight that SMPL joints do not represent the human skeleton, i.e., the joint locations are estimated based on a regressor that predicts their location as a function of the body shape [4]. However, the biofidelity of joint positioning is an improtant concern from both multibody dynamics and injury biomechanics perspectives [15].

More generally, this study demonstrates the importance of task specific approaches, i.e. making adaptations to existing deep learning techniques when applying them to defined tasks. This method overcomes an issue for traumatic injury biomechanics relating to the penalisation of unnatural poses in estimators involving supervision, by relaxing pose and shape constraints in the latter part of the optimization. The study also highlights the difficulties in obtaining sufficient quality in-the-wild footage, due to occlusions, low lighting conditions, low spatial resolution (image/video quality), or low temporal resolution (framerate).