Deep learning techniques for human motion capture: an injury biomechanics perspective

Motion capture is the process of recording human motion, it can be used for a variety of applications including character animation, and interactive gaming in the entertainment industry, robotic motion control and planning, or biomechanical applications such as injury and performance analysis. Since the late 1900s motion capture has been used for planar (2D) biomechanical kinematic analysis [1]. Since then, a wide variety of 3D motion capture systems have been developed which allow for more detailed analysis. These can generally be divided into the categories of:

- marker-based systems.

- wearable sensor-based systems.

- markerless systems.

This post is focused on the recent emergence of markerless deep learning approaches, for context, and since the accuracy assessment of many of these modern approaches rely on comparisons to traditional methods, a brief introduction to marker-based, sensor-based, and markerless systems is also presented. Though body and joint positional accuracy are important considerations in all applications of motion capture, they are of notable importance for human biomechanical analysis e.g. traumatic injury biomechanics, or physiotherapy. For this reason, this review focuses on the current and potential uses of motion capture in the field of traumatic injury biomechanics. Notwithstanding the significant developments in this area driven by the aim of improving motion realism in the entertainment industry.

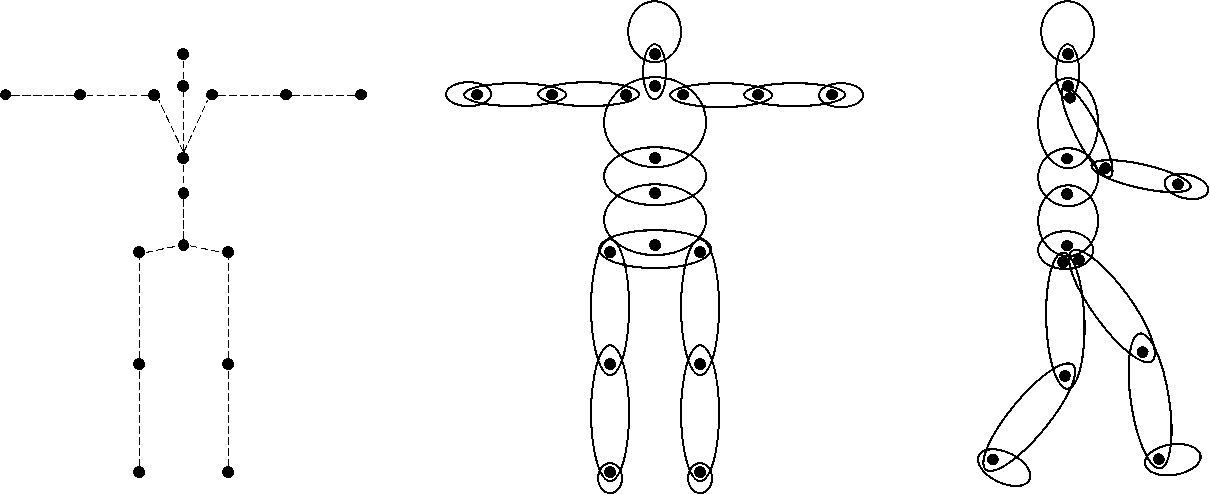

The operating principles of motion capture generally involve:

- the tracking of human body keypoints which correspond to anatomical joint positions.

- inference of tracked keypoint locations to body kinematics by use of a defined kinematic chain i.e. a hierarchical chain of links and joints.

These kinematic chains often involve the use of physically constrained joints, i.e. joints with less than 6 degrees of freedom (DOF). By taking estimates for link inertial properties i.e. body segment mass distributions, and creating a multibody system and applying inverse dynamics, the captured motion can be used to calculate dynamic information. Internal muscle response is also an important consideration and is an active research area for applications such as gait analysis, and traumatic impacts [2]. Without consideration of the internal muscular forces and torques exerted during human motion, impact loads can be estimated; this approach is commonly referred to as ragdoll physics in the animation industry, and is commonly used in biomechanical applications which do not involve a significant amount of human controlled motion, e.g. road traffic collisions (RTCs) [3], or sports scenarios involving impact to an unaware player [4]. Injury metrics have been developed which allow predictions of injury severity by body region based on their kinematic/dynamic response in collisions [5]. Most injury criteria are based on accelerations, relative velocities or displacements, or joint constraint forces, and need some mathematical evaluation of a time history signal. For inverse dynamics calculations, the accuracy of kinematic measurement is an important first step in biomechanical applications, as errors in joint position estimates propagate; resulting in even larger errors in dynamic estimates. Deep learning approaches applied to in-the-wild videos may allow for a more detialed understanding of impact kinematics/dynamics, e.g. [6].

Traditional motion capture methods

Optical or optoelectronic motion capture systems, such as Vicon [7], OptiTrack [8], Motion Analysis [9], and Qualisys [10] involve the tracking of passive retroreflective markers placed on a human subject, using multiple calibrated high-framerate cameras (>200fps) with light emitters (usually infrared). Active marker-based systems also exist, which use LED markers in place of passive retroreflective markers, eliminating the need for light emitters [11]. These systems obtain 3D positional cartesian coordinates, i.e. 3 degrees of freedom (3DOFs) for each marker by time of flight and geometric triangulation. Vicon is the most widely used passive marker-based system and is used as a proprietary eponym. Underlying skeletal joint positions and orientations (6DOFs) can be automatically estimated by inference from external markers [12]. Joint positions are calculated using groups of markers that move in the same way, with a minimum of 3 markers needed per joint to infer 6DOFs. These joints are positioned to approximate the human skeletal structure, and their kinematic nature with differing degrees of freedom (Free Joint: 6DOF, Ball Joint: 3DOFs, Hardy Spicer Joint: 2DOFs, Hinge Joint: 1DOF) limit the axes that the links are free to rotate about; effectively reducing unrealistic motions [13]. Custom kinematic skeleton formats may also be created [14]. Some marker-based systems have additional biomechanical analysis features; for example, Vicon has a plugin gait feature for calculation of lower and upper body dynamics such as joint forces, moments, and powers [15], [16].

![]()

There are also a variety of alternative motion capture systems that involve markers/sensors, including:

- inertial systems involving the use of inertial measurement units (i.e. combined gyroscope(s), and accelerometer(s)) [17], [18].

- mechanical systems involving the use of an instrumented exoskeleton (with sliders and potentiometers) [19].

- magnetic systems involving both magnetic sensor markers and a magnetic field generator [20].

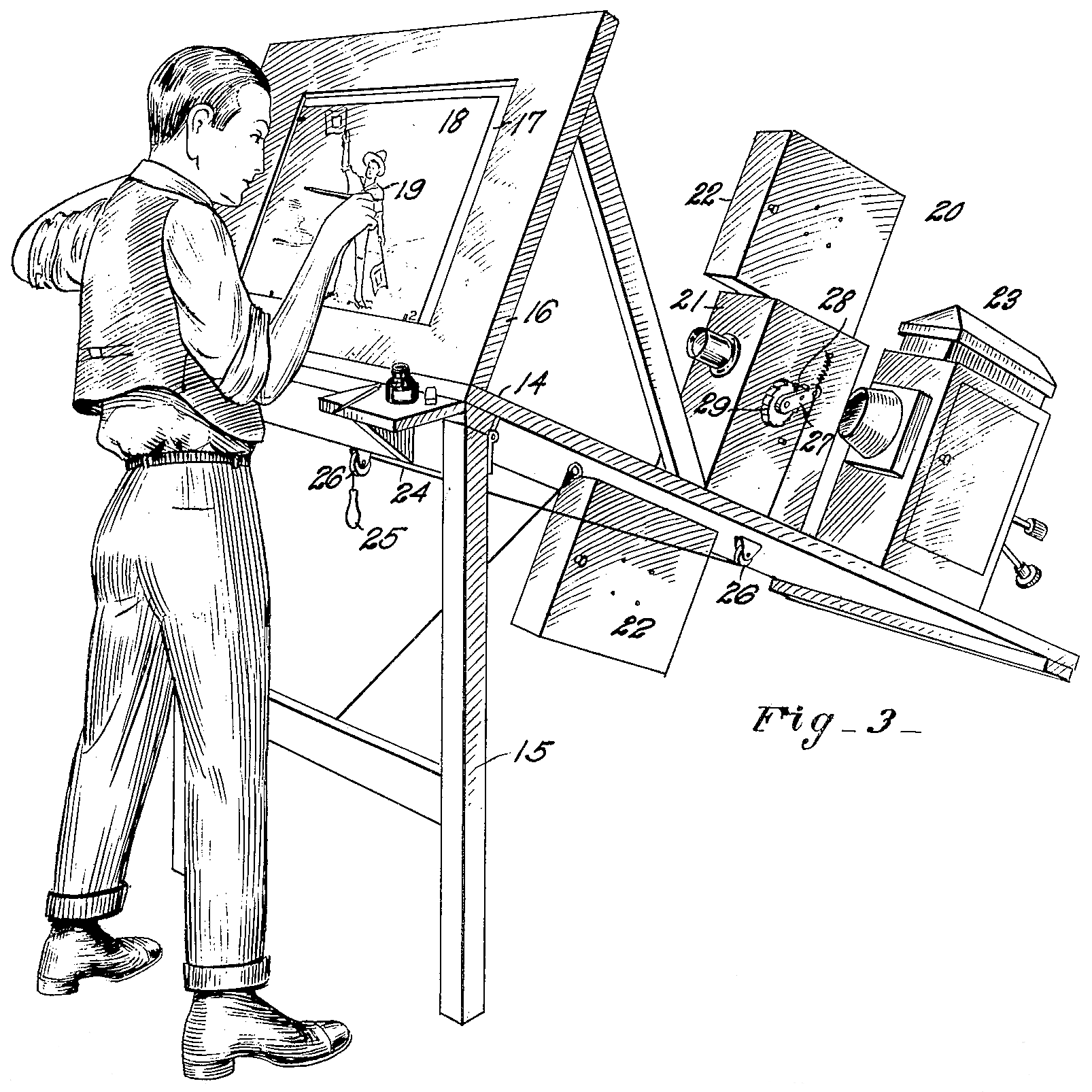

Though the accuracy of many of these marker/sensor-based systems are high; they are prohibitively expensive for many, and the experimental setups are unsuitable for many in-the-wild biomechanical applications. Markerless motion capture systems allow for more natural subject motion and aim for capture in less experimentally constrained environments (i.e. outside of a motion capture laboratory) [21, 22, 23, 24]. The first human motion capture system, the Rotoscope, invented by Max Fleisher in 1919, was in fact a markerless system. The system involves manual tracing of character outlines for individual frames of an image sequence. Most famously, this system was used by to animate human and equine gait [1].

More recent computer-based methods exist which employ spatially calibrated multi camera setups; streamlining the process and allowing for 3D analysis to be performed. These systems may be automatic e.g. [21, 24] or require manual annotation [25]. Cameras involving both colour and depth maps (i.e. RGB-D cameras) such as the Microsoft Kinect, or depth cameras alone, have the potential for accurate single-camera motion capture. Though the accuracy of the native software in the Kinect V2 is inadequate for many biomechanical applications, there have been efforts to improve upon the accuracy of the Kinect’s skeletal tracking capabilities, all in some way involve 1) fusing of multiple sensors, and 2) optimizing certain parameters to achieve more realistic motions. One physics-based approach (using 3 fused Kinect V1s) utilized body segment mass estimates from the Kinect depth sensors, insole pressure sensors, and optimization of the equations of motion [26]. Another approach that achieved a similar, albeit slightly lower level of accuracy involved imposing ellipsoids on body segments based on a mesh and minimizing cross over between them, and joint rotation angle boundaries (using 2x Kinect V2s) [27]. This approach did not involve the equations of motion and did not require the use of any wearable/external sensors. Comercially available softwares such as Ipisoft [28] also exist which allow for the use of multiple fused depth sensors in a relatively inexpensive and accurate motion capture setup.

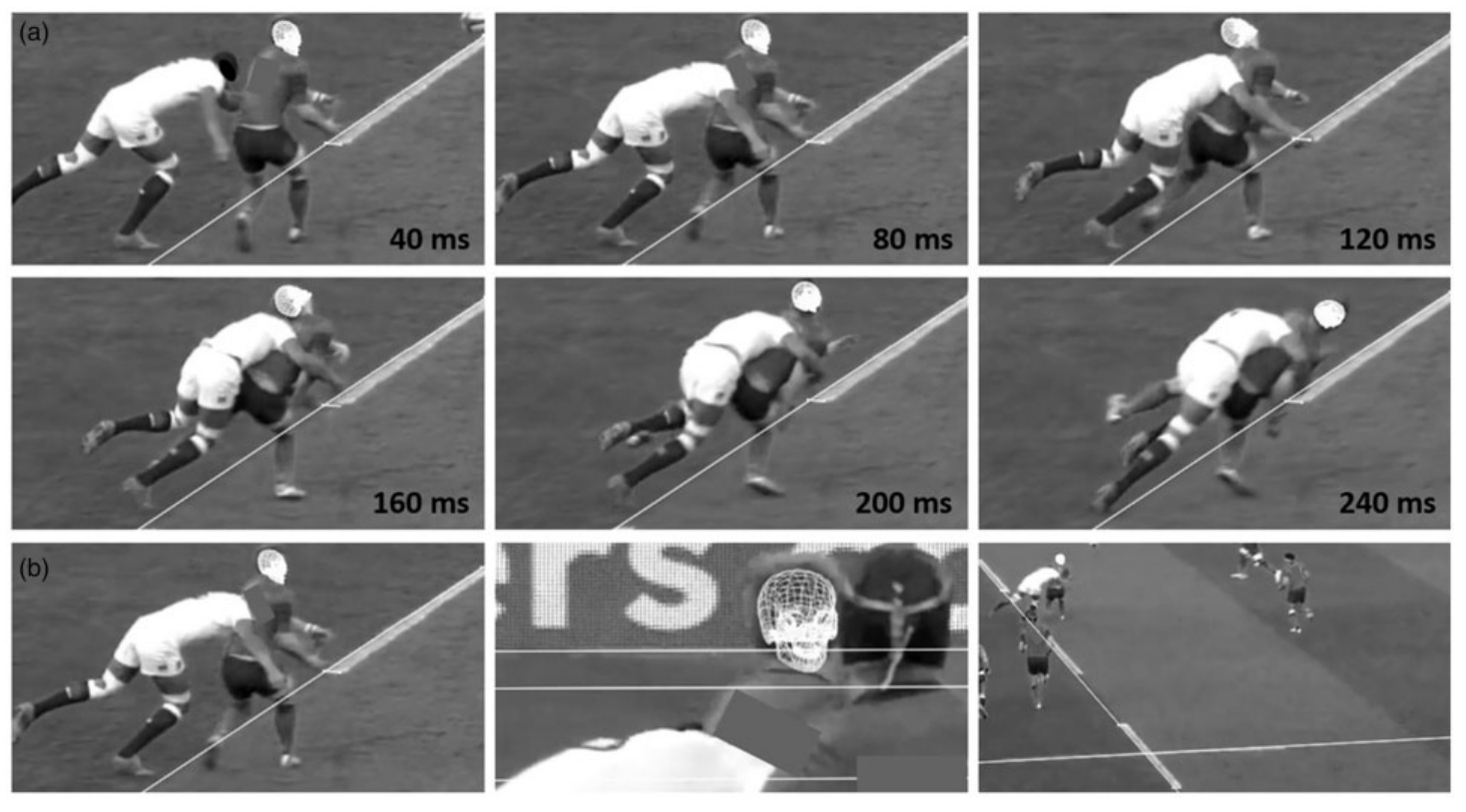

However, the requirement of multiple RGB-D sensors makes a system such as this unsuitable for in-the-wild biomechanics applications. One markerless method involving manual annotation used in the realm of biomechanical research, Multibody Image Matching (MBIM), has allowed for extraction of 3D pose from multi-view in-the-wild videos e.g. [4].

Though MBIM achieves high accuracy for certain applications [28], it requires multiple views of the scene, is labor-intensive, and is unsuitable for real-time applications.

Deep learning approaches

For (near) real-time and in-the-wild applications there is a need for automatic 3D tracking of joint positions using simple inexpensive cameras. Deep learning has recently been applied in this area with great success. These approaches have allowed for robust and fast (multi) human pose estimation outside of laboratory conditions. Generally, these systems involve the training of a model with prior ground truth data. Pose estimation approaches can be categorized as:

- bottom-up approaches, which first find the keypoints and then maps them to different people in the image.

- top-down approaches, which use a mechanism to detect people in an image, apply a bounding box around each person, and then estimate keypoint configurations within the bounding boxes.

Many deep learning approaches to 2D pose estimation have been developed [30, 31, 32, 33]. Due to its accuracy and robustness, Openpose is widely considered to be the state-of-the-art method for 2D multi-person pose estimation [29]. Openpose is a bottom-up approach that uses Part Affinity Fields (PAFs), i.e., flow fields that establish pairwise relationships between joints.

However, a more recent top-down approach HRNet outperforms Openpose slightly by retaining a high-resolution image representation throughout the training process [31].

3D pose estimation methods generally employ a 2D pose estimator as a backbone, and use techniques to project these into the 3D realm. For multi-camera setups, a simple approach involves geometric triangulation, i.e. exploiting the knowledge of camera intrinsic and extrinsic parameters of a camera to triangulate 2 or more views of a keypoint into 3D space [34]; in fact, Openpose contains a module for this [35].

A promising approach which does not require pre-defined calibration parameters, learnable triangulation, includes this geometric triangulation into the architecture [36].

3D single-camera approaches have also been developed e.g. [37, 38, 39]. GAST-Net (Graph Attention Spatio-Temporal convolutional Network) is the state-of-the-art method, and addresses problems experienced around occlusion and depth ambiguities in previous methods by including spatiotemporal information (i.e. learning kinematic constraints such as posture, 2nd order joint relations, and symmetry) [39]. GAST-Net has achieved joint positional accuracy within a few centimeters of marker-based motion capture methods for certain motion protocols, and outperforms previous methods particularly in cases involving heavy self-occlusion and fast motion.

3D pose and shape estimation methods also exist, which allow for the inclusion of body shape predictions. Combined body pose and shape estimation is useful from an injury biomechanics perspective; with both kinematics (pose) and estimates for body segment inertia tensors (inferred from the body shape estimate) inverse dynamics can be performed, which may allow for more detailed injury predictions. The most promising approaches involve the use of a statistical human body shape model (e.g. SMPL [40], GraphCMR [41], SPIN [42], STAR (state-of-the-art) [43]), i.e. a skinned vertex-based model that accurately represents a wide variety of body shapes in natural human poses, developed via dimensionality reduction techniques i.e. Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

The current state-of the art 3D pose and shape estimation method VIBE [44] estimates SMPL body model parameters for each frame in a video sequence using a temporal generation network, which is trained together with a motion discriminator i.e. AMASS [45].

Current deep learning based pose/shape estimators are known to have limitations in terms of the bounded human pose/motion space used in training data, e.g., insufficient images of non-upright poses in COCO (an annotated pose dataset) causes failure in pose estimation [46]. A key requirement of these methods is that they are robust to in-the-wild examples; this may be achieved with greater variety in the training data, and relaxing pose and shape constraints to allow for less ‘natural’ motions.

The latter has been recently and successfully applied to characterise pedestrian pre-crash posture [47].

See my blog post: ‘A novel deep learning based approach to determining pedestrian pre-crash posture’

Conclusions and future directions

The trajectory of advancement in deep learning motion capture methods has mirrored that of traditional ones. Early iterations of deep learning-based motion capture have focused on planar joint position estimates from monocular viewpoints. These systems have achieved remarkable accuracy, and consequently, more recent efforts have been pushing towards the 3D realm. The accuracy of these systems are currently below that of gold standard marker based systems, or other markerless systems involving depth sensors or multi-camera setups, however the gap has been reducing. Deep learning based pose and shape estimation methods also present the unique opportunity of extracting 3D kinematics and dynamics from in-the-wild images and videos which has applications in many fields. This is an emerging research topic, and with the transformative effects deep learning approaches have had in other fields in the near future we can expect to see significant improvements.